In the midlands of 1950s Ireland, art was not considered a vehicle for personal expression. It was decorative, utilitarian—meant for book illustration, theater sets, business signage. At best, it emulated English landscape painting with polite, conventional brushwork. Into this stifling atmosphere came a boy whose drawing ability seemed almost otherworldly.

Patrick Graham was entering competitions he didn’t know he’d been entered into—submitted as a lark by others who marveled at his facility. At 16, he became the youngest person ever awarded a scholarship to the National College of Art in Dublin. But this prodigious gift would nearly destroy him before it could transform Irish painting forever.

Now, at 82, Graham’s work returns to Pasadena for “Patrick Graham: Notes from Ireland,” which opened on February 1 and is now on view at Jack Rutberg Fine Arts—a gallery that has represented him internationally since his dramatic American debut in 1987. The exhibition, running through April 18, marks a homecoming. In 1991, Pasadena City College brought Graham from Dublin as Artist-in-Residence. On that occasion, major exhibitions of Graham’s work, and lectures by the artist, were presented at both PCC and the Rutberg Fine Arts. The gallery has been instrumental in supporting museum exhibitions of Graham’s art throughout the U.S. and Ireland.

“Patrick is very simply, in my view and the view of a great many, the most important artist in Ireland’s history,” says Jack Rutberg, the gallery’s director. It’s a claim supported by Ireland itself, which inducted Graham into Aosdána in 1986—a government affiliation limited to 250 living artists in music, literature, architecture, choreography and the visual arts, whose works have made outstanding contributions to the creative arts of Ireland.

But the journey to that recognition required Graham to confront not just his own demons, but the oppressive weight of Irish history itself.

Ireland in Graham’s youth bore the scars of centuries under British occupation. The one distinction the Irish were allowed to maintain was their Catholic faith—and the Church, filling that void of power, became all-consuming. The result was what Rutberg calls “profound repression” that marked entire generations.

At the National College of Art, Graham’s genius drew immediate adulation. But there wasn’t a single volume in the library on modern art. Picasso wasn’t discussed, wasn’t even whispered about. Everything centered on academic mastery of old masters—techniques that had nothing to do with life in Ireland or the broader modern world.

When Graham encountered a touring exhibition of German Expressionist Emil Nolde, his first reaction was rage. But privately, he recognized a truth in those dark, mysterious works that his own technically perfect drawings lacked. “He recognized that the facility that he had naturally… was just that, just mere facility,” Rutberg says. “There was no truth, no discovery in it.”

Unable to reconcile his talent with authentic expression, Graham turned to alcohol. He stopped drawing for years. There were blackouts, near-death experiences, a priest reading last rites over his comatose body.

After several attempts at sobriety, Graham placed himself in a mental hospital. There, a Jesuit priest and psychologist worked with him to understand that his gifts “needed to be shared for the betterment of others.”

The turning point came unexpectedly. Sitting at a picnic table in the hospital yard, Graham noticed another patient across from him—someone staff called “the collector” because he gathered twigs and string. Graham idly sketched a perfect portrait. When he placed the drawing in front of the man’s face, there was no reaction.

Graham began to seethe—not at the patient, but at himself. “Why should he react?” he realized. “I’ve shown him a mirror. There’s no truth, there’s nothing, there’s just nothing to it but facility.”

What happened next changed Irish art history. Graham attacked his own drawing, working into it viscerally, abstracting it, seeking something beyond mere representation. That moment, Rutberg explains, “some believe was the birth of modern art in Ireland.”

His first exhibition after emerging from the hospital was titled “Notes From a Mental Hospital and Other Love Stories.” It was both reviled and celebrated, but for an entire generation of young Irish artists, Graham had made personal expression possible.

The work’s impact extended far beyond Ireland. Art historian Donald Kuspit declared Graham’s paintings “masterpieces… on a grand physical, emotional and intellectual scale.” Peter Selz, the legendary curator who founded UC Berkeley’s art museum, said Graham “confronts the viewer with drawings and paintings of shattering force.”

Rutberg first encountered Graham’s work through actor Vincent Price, an avid art collector who discovered Graham’s paintings in London. “I saw Patrick’s work and I was taken by them,” Rutberg recalls. “I didn’t quite understand them and I didn’t even understand why I was saying it, but I said, ‘I’d like to learn more about this one artist.’”

The 1987 Los Angeles exhibition was unlike anything Rutberg had experienced. “I could see one of the people in a visiting couple motioning, ‘Let’s get out of here,’” he remembers. “An hour later, they’re still in the exhibition and felt compelled to acquire a work.” At one Graham exhibition, Rutberg’s staff stopped counting at 30—the number of people whose eyes were tearing or openly crying. “They did not understand why,” he says simply.

Perhaps it is not surprising that, in light of the gallery’s impactful presentations of Patrick Graham and major artists from Mexico, Spain, Austria, and the United States, in 2023 the International Art Association/USA–an organization working in partnership with UNESCO–honored gallery owner Jack Rutberg with its first Lifetime Achievement Award, calling him “a legendary gallerist and a genuine Los Angeles treasure.”

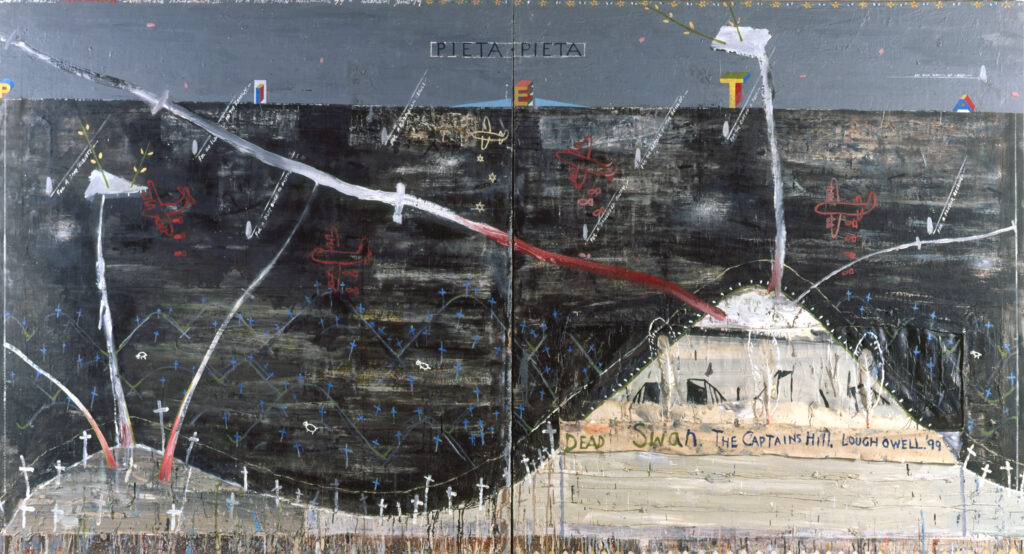

The current exhibition, “Patrick Graham: Notes from Ireland,” spans several decades of Graham’s work. The paintings and mixed-media works on paper—combining ink, graphite, paint, and torn collages of Graham’s own earlier drawings—deal with “humility, vulnerability, dismantling the dogma of “great truths” while recognizing the small ones, which are forever changing.

Graham’s work celebrates what was forbidden in Ireland for generations. “Sexuality is very much a part of it,” Rutberg notes, “because it celebrates that which has been forbidden.” As late as the 1960s, according to a James Joyce scholar

who attended the exhibition opening, there were virtually no books on Joyce available in Ireland.

“That’s the realm, that’s the starting point from which this art emerges into possibilities,” Rutberg says.

For Graham, the journey from prodigy to alcoholic to Ireland’s most transformative painter represents more than personal redemption. It embodies a nation’s emergence from repression into authentic self-expression—a journey that required confronting darkness before finding truth.

********

“Patrick Graham: Notes from Ireland” is now on view at Jack Rutberg Fine Arts, 600 South Lake Avenue, #102, Pasadena. The exhibition runs through April 18. Gallery hours: Tuesday-Friday 10-6, Saturday 10-5. Free admission and parking. (323) 938-5222, jackrutbergfinearts.com.